“Margaret Leeson and the Economics of Sex Work in 18th Century Dublin”

Margaret Leeson, a.k.k Peg Plunkett. Unknown artist, 1760.

Sex work is often euphemistically referred to as the world’s “oldest profession.” Yet, in its historical context, it is rarely studied or understood as a valid profession, subject to financial scrutiny, or given a place in conversations about economy and industry. More commonly discussed in terms of urban vice, morality, or depravity, the world’s oldest profession is not often treated like the business that its participants considered it to be, nor have the financial records of sex workers been broadly compared to those practitioners of more recognized professions. Indeed, the very vocabulary around sex work has served to undercut the professional choice it represented for many women, with terms such as “prostitute,” “whore,” and “bawd” serving not only to identify practitioners of the profession, but to slander women outside it – a feat hardly accomplishable with “apothecary” or “merchant!” This shadow over the profession, often discussed in whispers and coded terms, makes it particularly hard to study. However, in 18th century Dublin, sex workers and their clients treated this profession like the commodity that it was, and the service as which it was advertised.

Enter Mrs. Margaret Leeson, alias Peg Plunkett, a notorious Dublin brothel keeper and the city’s “most reputable courtesan,” who was a “celebrity madam” for most of the latter decades of the 18th century. In 1795, suffering from poor health and in dire financial straits, Leeson published the first volume of her salacious memoirs. Having attempted unsuccessfully to retire by calling in the debts former clients owed her, Leeson’s plan was to capitalize on the moral aversions to her profession, threatening to name those who had patronized her establishment over the years unless they made good on their financial obligations to her.

Cull or Cully

noun

slang or colloquial, now rare

one who patronizes a sex worker; a female sex worker’s male client

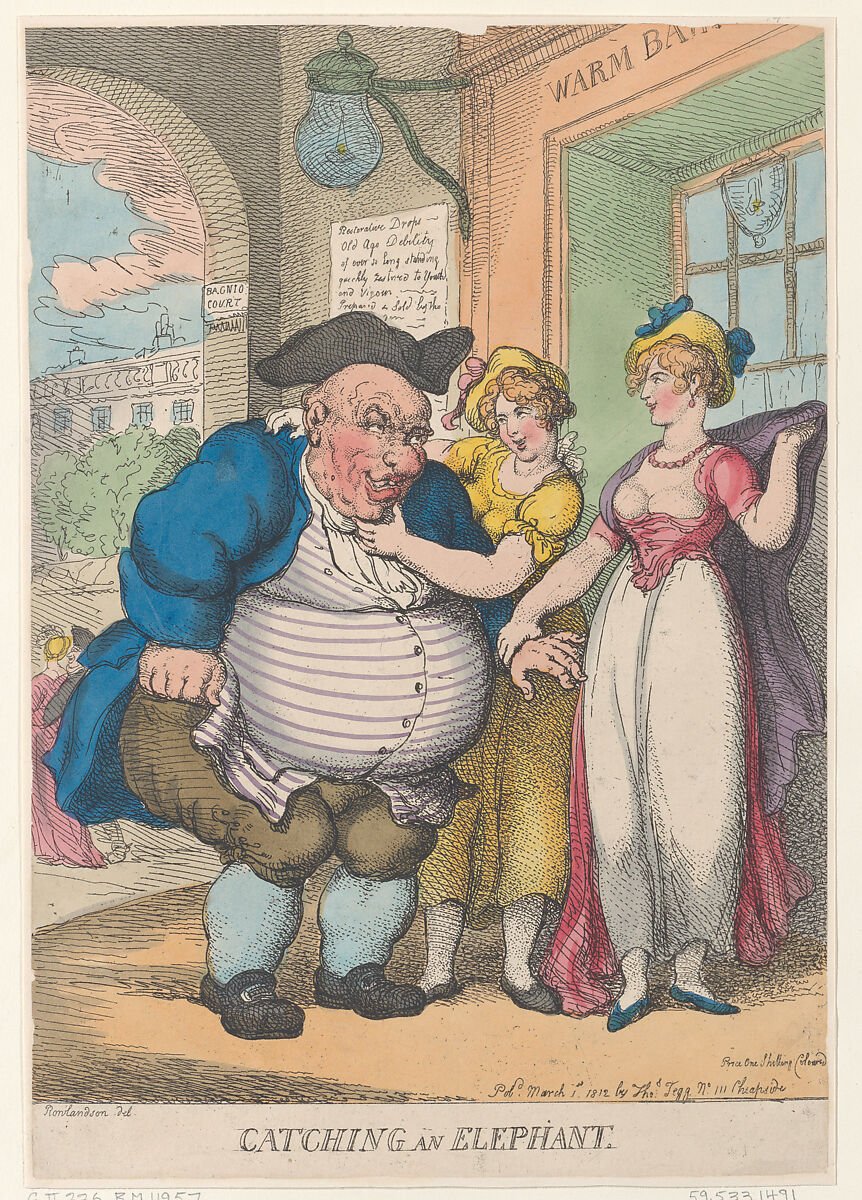

Image: Catching an Elephant by Thomas Rowlandson, 1812

It was an attempt to raise enough money to procure herself a little comfort at the end of her long and storied life, and while fewer of her culls paid their debts than she would have liked, the memoirs themselves were quite successful. Widely recognized as being at the top of her profession, Leeson’s account is a careful mingling of business and pleasure. With so many of her culls identified, it is possible to give some estimate of the economic clout of her clientele, and to draw some reasonable conclusions about where, in the economic spectrum of 18th century Dublin, elite sex work featured. While the memoirs span decades and include Leeson’s escapades with prominent figures in Irish society, including the wealthy and titled, for the purposes of this presentation, we will confine ourselves to the finances of working professionals who Leeson lists as having patronized her Pitt Street establishment.

A Note On Currency

All currency values given in this presentation are in Irish pounds. Most of the primary sources cited use references to Irish currency of the 18th century, and I have converted any other references to those units for the sake of consistency.

18th Century Currency 21st Century Currency

£100 Irish pounds $213,000.00 US Dollars

€174,340.10 Euros

£150,431.25 Pounds Sterling

The non-titled men who were known clients of Leeson’s Pitt Street brothel came from a variety of professions, ranging from doctors, soldiers, merchants, and members of the Anglican clergy. While it is not possible to state the precise incomes and financial status of every individual client concerned, we can make a few inferences based on a general understanding of the professions they represented. An Anglican clergyman serving a Dublin parish in the 1780s could expect an average annual income of about one hundred and fifteen pounds, which did not include the value of his parish house, or any fees he received for services not compassed by his salary, such as performing weddings and funerals.

Those who took the King’s shilling depended upon their rank to increase their shillings. An infantry captain earned a salary of between fifty two and thirty-five pounds annually, depending upon the size of their companies. This figure does not include the various living expenses paid by the military. Cavalry captains fared somewhat better, drawing salaries of anywhere between one hundred and ten and sixty-four pounds, again, depending upon the size of the company, and not inclusive of military living expenses. Officers could expect to pay several hundred pounds for their commissions in the first place, and in order to even qualify for such a purchase, potential officers had to offer proof of their estates. A captain must either have had a personal fortune of a hundred and eighty-four pounds, be heir to a fortune of three hundred and sixty-nine pounds, or the younger son of a man with a fortune of at least five hundred and fifty-three pounds. A lieutenant’s requirements were as follows: either a real estate of at least forty-six pounds, a personal estate of nine hundred twenty-two pounds, or a real and personal estate valued together at eighteen hundred and forty-four pounds. Captains and lieutenants were the ranks most commonly mentioned amongst the Pitt Street callers.

The merchant class grew in wealth and affluence during the 18th century as well, putting them amongst the classes of those who could afford to visit elite sex workers. A textbook on trade and business published in 1748 suggests that an average trader’s worth in ready cash and moveables would be valued at about two hundred eighty-five pounds, which would not have included any real estate holdings or other investments. Wine merchants found the 18th century to be a particularly lucrative era, if the prices for beverages listed in Leeson’s memoirs are any indication. Meanwhile, the booming flax and linen industries meant that merchants such as Waddell Cunningham – a frequently named figure in Leeson’s memoirs – had the potential to accrue massive fortunes. Upon his death, Cunninham’s estate in Ireland was valued at 60,000 pounds.

Surgeons practicing in 18th century Dublin under the auspices of the Royal College of Surgeons charged fees for their services, as overseen by the College. Apprentices or pupils paid accredited surgeons anywhere from two to three hundred pounds to acquire their own credentials. Surgeons were limited to accepting no more than two pupils at any given time. As their practices, like sex workers’, were dependent upon word of mouth and a loyal clientele, their fortunes could fluctuate significantly.

So, where do the finances of elite sex workers feature in this loose hierarchy? Conceptually, they might more closely resemble that of local shopkeepers, in that they offered goods and services at fairly standard rates, but were dependent upon a loyal clientele, a solid reputation for quality, and word of mouth marketing. Leeson indicates that the rates she and her employees charged for sexual services were fairly stable, and cites specific examples of fees paid. Leeson herself charged 10 guineas for a single act in which a client experienced “every perfect enjoyment” with her, but did not require the overnight use of the bed used in the experience, which would have incurred a separate expense. An unnamed client from Limerick was charged £2, 16s, 9d for “a night’s lodging, a girl, and a bottle.” Another client identified only as “Captain Longnose” racked up a bill of £18, 6s, 6d for a bottle of wine and Leeson’s “recommendation of two ladies.” In addition to sex workers in Leeson’s direct employ, she also provided what we might call today co-working space for freelancers. Three extremely high-end brothel workers hosted by Leeson earned three hundred pounds each over the course of nine months – of which Leeson took a cut for lodging them and promoting their services. Leeson herself received an offer from a linen merchant who wished to become her keeper, promising her £100 a year for life, and the purchase of a new house. He gave her £100 in advance while she was considering his proposal, and though she ultimately declined, she kept the money.

Sexual acts were not the only services available for purchase in elite brothels. Ambiance was of paramount importance to the experience, and madams such as Margaret Leeson also offered food, wine, and lodging for a price. Brothels were considered one of the few places where 18th century men could indulge in luxuries without drawing accusations of emasculation or homosexuality. On one occasion when a gentleman caller visiting Pitt Street did not indulge in the primary services on offer, he paid 5 guineas for the privilege of sitting in Leeson’s company and conversing genteely with her. One client from Kerry required merely a week’s board and lodging, for which he was charged £5, 13s, 9d. Ambiance extended to the objects within Pitt Street. A client from Tralee once took a fancy to a gold seal that Leeson owned, and she sold it to him on the spot for £4, 11s. Particularly elite madams with solid financial reputations might also act as informal money lenders, settling the debts of their clients with the understanding that they would be amply repaid and compensated. Leeson notes multiple instances in her memoirs when she either stood as surety for a client’s debt, loaned money, or recovered items from pawnbrokers on behalf of either her clients or employees. When an unnamed client needed to quickly discharge a debt of 30 guineas, Leeson was easily able to supply him with ready cash. Leeson prided herself on having a reputation for discharging debts for loyal clients, paying out sums ranging from £4 to £19 at a moment’s notice, noting that she kept ample cash in her Pitt Street residence for such occasions. Another client, identified as Mr. Blinker from Thurles, received a loan from Leeson for £34, 6s. When Leeson hired a sex worker named Kitty Gore, she was obliged to redeem Gore’s clothing from a pawnbroker, to the tune of 7 guineas. Leeson was also willing to extend credit for particularly wealthy clients. A surgeon spent what one can only imagine was a particularly decadent week enjoying the pleasures of Pitt Street, running up a debt of £100 for what Leeson terms “wine, beds, and –” something she considered unprintable. While Leeson ran into financial difficulties later in life due to her inability to collect on the various IOUs she held, it is clear that she had expected to be compensated with interest. A sex worker named Elinor West left Leeson’s employ £50 in her debt, but repaid Leeson £60 a few months later. When another elite madam named Mrs. Robinson visited Dublin and found herself short of cash, Leeson supplied her with the trifling “gift” of 20 guineas, only to be repaid with £50 worth of calico and a finely printed book upon Robinson’s return to her home in London. Leeson was touched by the largess of the gesture, and bemoaned the fact that so few people in her debt had behaved so honorably. Leeson enumerates the many debts that she was unable to collect from her clients, expressing bitterness over the financial misfortunes she suffered by being too tender-hearted.

Progress of a Woman of Pleasure by Richard Newton, 1794

Other clues about the state of elite sex workers’ finances can be gleaned from the expenditures Leeson lists in her memoirs. As glamorous presentation comprised a large part of the elite sex workers' business model, attention must be paid to expenditures that reference clothing and jewelry. The most direct reference to outfitture given in an anecdote when Leeson took her newest protegee shopping for a new wardrobe to the value of £100. Leeson makes further mention of the purchases made by other elites of her profession, such as the aforementioned Mrs. Robinson, who spent £500 on plate and 35 guineas on shoe buckles. Sadly, Leeson does not list the prices of every item she or her contemporaries purchase over the course of her memoirs, but the items she does mention were considered luxury goods.

Leeson also alludes to the numerous servants in her employ. Given the complexities of dressing one’s person and one’s hair in the height of 18th century fashion, Leeson and her elite contemporaries employed lady’s maids – at least one would have worked at Pitt Street. An elite lady’s maid in the 1780s could expect to make about £15 annually, depending on experience and duties. Upon opening Pitt Street Leeson hired a pair of footmen whose services would have cost her about £16 each, annually. She also purchased a coach and four – an enormous expense, to say nothing of the stabling, care, and feeding of the horses, which would have run her at least £36 a year. She also hired a coachman to drive it for an annual salary of around £13. Leeson specifically states that she hired “a complete suite of servants,” indicating that she employed both a cook and a housekeeper, to whom she would have paid annual salaries of about £10 and £14 respectively. While some brothel keepers expected novice sex workers to occasionally act as housemaids, Leeson disparages that practice; she relates with much disapproval the tale of sex worker Nancy Hinds, who began her career in a brothel operated by Mrs. Ord of Great Britain Street, where she was paid merely 3 guineas a year. Average salaries for housemaids were about £7 a year, and Leeson employed at least two. While it is unclear how many other servants would have worked at Pitt Street, elite brothels with reputations such as Leeson’s generally employed at least one laundress, who could expect to be paid around £9 annually. Leeson also mentions hiring a dulcimer player named Isaacs, stating that she paid him 50 guineas a year to play for her on a weekly basis.

High Life Below Stairs by John Collett, 1763

Leeson gratifies her readers with a lengthy description of the manner in which she furnished her Pitt Street establishment. With her customary (im)modesty, Leeson declares that she had the house “furnished in the most superb and luxuriant style, with every matter that genius or fancy could suggest to the most heated and eccentric imagination.” Although Leeson does not reveal the price tag on her extravagant furnishings, the cost of furnishing an entire townhouse would have run about £100-200 based on contemporary records. Given that Leeson’s profession required that she purchase multiple beds, her costs were higher than average, probably closer to £300. Leeson herself never states the exact value of her assets, although at one point, she mentions that she had “several hundreds” in the bank after discharging all of her debts. She also reports that it was rumored that she had £10,000 in the bank. While she concedes that this rumor was untrue, the fact that it was widely believed due to her luxurious mode of living is some indication of her reputation as a successful professional in her field.

However, the greatest resource available for comparing the financial status of elite sex workers and their clients is perhaps real estate. The average annual value of property on an acre of land in Dublin County during the late 18th century was about £22, and the city centre properties occupied by Leeson, her contemporaries, and her professional class clients would have been significantly smaller than an acre. By comparing the property values of elite sex workers’ domiciles with that of their clients, we are able to make one-to-one comparisons, giving historians some sense of overall financial status and hierarchy. We do not know the exact number of Leeson’s Pitt Street residence, but the average annual value of property was about £10. Her rival, the parsimonious Mrs. Bridget Ord, lived on Great Britain Street, where the average annual property value was £16, as did the sex workers Nancy Hindes and Mrs. Wrixon, who kept a brothel with her husband. Another contemporary, Mrs. Palmer, had an establishment at King Street close to the fashionable St. Stephen’s Green, where the average annual value was £9. In Trinity Street, where Mrs. Brooks kept a brothel, the average home was valued at around £14 annually. Leeson also names Mrs. Grant, who kept two different houses on Stafford Street at various points in her career; the average property value there being £14.

Map of Dublin by Robert Pool (artist), John Cash, John Lodge, and Isaac Taylor, 1780

Of the identifiable professional-class clients who patronized Leeson and her contemporaries, we know of at least three who lived on Grafton Street. An apothecary named Philip Hatchell lived at number 45 in a home valued at just over £35. The son of Peter Le Favre, a perfumer, lived at number 54; the family home was valued at at little over £36. At number 68 lived a grocer named Myles Duignan; his home was valued at £49, making him the owner of the highest valued home of all the non-titled clients listed. A client with a similarly high property value was the son of tea merchant Philip Higginson, whose home at 26 College Green was rated at £38. John Usher and William Jenkins, were both apothecaries who lived on Dame Street in homes valued at £37. The surgeon Alexander Graydon lived at 7 Jervis Street in a property valued at £35. His fellow surgeon, Charles Bolger, lived at 13 Suffolk Street; his home had an annual value of £24. Several of Leeson’s clients lived in Capel Street where the average residence was valued at about £18 annually.

From these data sets, a number of inferences are possible. At the very least, we can conclude that, on average, sex workers spent less on housing than their clients. This seems to suggest that the clients in this sample were wealthier than the sex workers they patronized. However, this assessment is complicated by a number of factors. As has been previously discussed, Leeson’s household expenses, which were based on the necessity of creating ambiance through conspicuous displays of luxury goods, were very high. A merchant or surgeon with a similar income might not feel as compelled to spend so lavishly on his own home. Sex workers, moreover, were expected to maintain expensive wardrobes, including jewelry. Women’s clothing, which required larger volumes of fabric, was more costly than men’s clothing of the 18th century, and style-makers such as Leeson and her contemporaries would have felt compelled to ensure that they were always attired in the latest fashions, whereas an apothecary’s reputation would not suffer if he wore the same greatcoat two seasons in a row. Rather the contrary; the 18th century Irish bias against the creep of Continental macaroni fashion compelled men to dress more simply. Women in general, and sex workers in particular, were also much more voracious consumers of luxury goods, particularly imports from the Continent. And of course, the fact that elite sex workers were, in turn, the clients of merchants who sold luxury goods, meant that, as fellow professionals, the relationships were symbiotic. These variables, including the fact that some of Leeson’s professional class clients, such apothecaries and particularly merchants, would have had high overhead costs of doing business, make it difficult to ascertain exactly how much more affluent these clients were. While the comparison of real estate value between these working professionals is possible, it still only tells part of the story.

View from Blackrock Railway Station, by W. Wakeman, 1834

Perhaps the most telling indicator of Margaret Leeson’s finances was the manner in which she planned her retirement. Removing from Dublin city proper to the sea-views of the newly-fashionable Blackrock suburb, Leeson planned to join the ranks of leisure class families building villas along the fine new roads. Her new home, which she had built from the ground up, cost over £500 to construct – a substantial $1.6 million in today’s money; Leeson spent an additional £100 on it during her first year there. While she was unable to collect on the debts that she believed would have allowed her to live out her life in a fashionable and refined manner, Leeson was able to recoup over £600 from the sale of her memoirs, after expenses. At a time when few single women worked and even fewer with economic opportunities chose to personally engage in commerce, Leeson’s account proves that elite sex workers were uniquely positioned to attain personal wealth on par with that of their professional class male counterparts.

Appendix A: Currency Conversation and Estimated Property Valuation

The primary sources used in this paper that give currency values date from between 1755-1799. Most of these figures are given in Irish pounds, though some were given in pounds sterling. Where pounds sterling were used, I converted these figures to Irish pounds, using the conversion tables provided by Wyndham Beawes at 8.75, which, according to tables provided in John J. McCusker’s book, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600-1775, was the average conversion rate between the two currencies based on data available from 1750-1775. Further context into the value of the denominations used and suggestions as to the methodology employed were gleaned from the introduction to Thomas M. Truxes’s book Defying Empire. While this methodology is imperfect, so are the values given in Leeson’s memoirs, which span decades, as do the conversion rates for the figures she includes.

A slightly more complicated methodology was used in determining property values. In the absence of access to property valuation records from the latter half of the 18th century, I restricted my research to identifiable properties in Dublin that are listed in both Leeson’s memoirs (as edited and further identified by Mary Lyons) and the 1853 printing of Griffith’s Valuation, including only neighborhoods where property values remained relatively stable since the publication of Leeson’s memoirs. Indeed, nearly all the properties surveyed are in areas of Dublin 2 that have retained their value to this day. I then converted the residential values of the properties listed in Griffith’s to their late 18th century equivalent in pounds sterling, using the website MeasuringWorth.com. Having then obtained the desired property values in pounds sterling, I used Wynham Beawes’s tables of exchange to convert these sums to Irish pounds, using the aforementioned rate of 8.75, as it was the average for the latter half of the 18th century. While these values therefore constitute estimates and are therefore imperfect, they provide a workable scale of comparison between the listed values, and can also be compared to the value of other goods and services enumerated in Leeson’s memoirs, which are, as previously stated, given in Irish pounds, converted, when necessary, to the average rate of exchange.